Nalini Malani

Retelling Women’s Stories Through Vast Collection and Transformation of Images

- Name

- Nalini Malani

- Media

- Painting, Print, Installation, Film/video, Photography, Performance, Others

- Region

- India

- Year of Birth

- 1946

- Place of Birth

- Karachi (former British India, present Pakistan)

- Place of Residence

- Mumbai, India

- External Link

- Link to Art Terms

-

- Link to Regions

-

My whole endeavour is to make visible that which is invisible. That is my job as an artist. (Nalini Malani, 2001)[1]

Sources of International Acclaim

Nalini Malani is one of the most internationally active, recognized, and highly acclaimed Asian artists today, frequently invited to participate in international exhibitions and having solo shows at major museums worldwide. In 2023, she received the prestigious Kyoto Prize, an honor awarded to only two other Asian artists, Isamu Noguchi in 1986 and Nam June Paik in 1998. Both Noguchi and Paik were male artists based in the US, making Malani’s recognition as a female artist based in India extraordinarily significant.

While Malani began her career as a painter, she from the very start in 1969 worked as well with photogram (cameraless photography), film and animation. Since the early nineties she creates installations on a grand scale which she calls Video Plays, Video/Shadow Plays or Animation Chamber. In these she incorporates time-based media as video, iPad animations and rotating reverse painted Mylar cylinders. Although she was certainly a pioneer among artists in India working with installation, it should be emphasized that her practice is not a mere response to the spectacle-oriented tendencies prevalent at international exhibitions. Her distinctive spatial and theatrical moving image works have been notable for engaging with complex themes and inviting active audience participation.

Malani’s international acclaim stems not only from the impact of her artistic expression and exhibition techniques, but also from her steadfast commitment to one of the most urgent and vital issues of our time. This is giving voice to women, especially those who historically, and still today in the present sociopolitical context, have faced discrimination and abuse, yet whose suffering has been silent and protests unspoken.

Evolution Toward Shadow Play Installations

Born in Karachi (now in Pakistan) to a Sikh mother and a lawyer father whose family were Theosophist, Nalini Malani relocated to Mumbai (then known as Bombay) and later to Kolkata (then Calcutta) during the mass migration of Hindus to India following the 1947 partition of India and Pakistan. The family eventually settled in Mumbai in 1954. From 1964 to 1969, she studied at the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art, but dissatisfied with its European-style academic approach, she obtained a studio at the Bhulabhai Memorial Institute. There, she interacted with artists, musicians, and dancers including Gaitonde, Tyeb Mehta, M. F. Husain, and Nasreen Mohamedi, and worked on theatrical design. Her interest in film, an element that would later become central to her practice, also emerged at this time, as she watched Indian and Soviet films and studied the film theories of S. M. Eisenstein and Rudolf Arnheim. She held her first solo exhibition in 1966. From 1969 on she participated in the Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW) organized by renowned painter Akbar Padamsee. She was the most productive member with three short films (Still Life, Onanism and Taboo), a stop motion animation (Dream Houses) and a several series of cameraless photographs.

From 1970 to 1972, Malani studied in Paris, which was still feeling the aftershocks of the May 1968 uprising led by leftist students and workers. During this period, she engaged with the philosophies of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Roland Barthes, and Jacques Lacan, and attended lectures by anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, linguist Noam Chomsky, and Surrealist poet-anthropologist Michel Leiris. At the Cinémathèque Française, she viewed avant-garde films of the Nouvelle Vague (French New Wave) and thereafter met with directors such as Alain Resnais, Jean-Luc Godard and Chris Marker. In the visual arts, she was influenced by the radical Support/Surface movement that sought to dismantle the “bourgeois” institution of painting, as well as by post-revolutionary Mexican artists like Diego Rivera. These formative encounters with radical and experimental culture in Paris greatly expanded Malani’s artistic vision.

Choosing to continue her practice in her home country, Malani returned to India and continued making films, including a documentary on Muslim slums and Taboo, which explored gender issues within the village community in Borunda, Rajasthan State. Beginning in 1978, she maintained a studio in Mumbai’s working-class Lohar Chawl district (until 2003) [2], where the daily lives of ordinary people, surrounded by hardware stores and markets, became an important theme in her work.

In her painting practice, Malani was involved in two landmark exhibitions that marked turning points in Indian art history. The first was Place for People, held in Mumbai and Delhi in 1980–81, where she was the only female artist participating. This exhibition reasserted figurative expression, with references to traditional styles of Indian painting, within an art scene dominated by the abstract tendencies like those of the Progressive Artists’ Group. The second was Through the Looking Glass (1987–89), the first exhibition in India organized by women artists and featuring only women artists, which broke new ground in the overwhelmingly male-dominated art world. Malani initiated this exhibition after she visited in 1979 the A.I.R. gallery in New York run by feminists for women artists. Through the Looking Glass traveled to five venues all over India.

Malani subsequently ventured into time-based works that combined multiple media, including installation, theater, video, and performance. In her 1991 solo exhibition Alleyway, Lohar Chawl at Jehangir Art Gallery, she suspended reverse painted transparent sheets, allowing visitors to walk through them in her first interactive work. A more daring experiment followed in her 1992 solo exhibition City of Desires at Gallery Chemould. In her first installation utilizing both the walls and floor, she publicly painted directly onto the gallery walls and, in a performative act, erased the paintings herself. This approach encouraged dialogue with the audience while rejecting the notion of painting as a commercial commodity. In addition, it was a protest against the neglected state of the valuable 19th-century fresco murals in Nathdwara [3], northwestern India, which at the time were left damaged without preservation efforts.

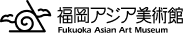

A pivotal moment connecting to Malani’s later performance-based works came in 1993. When actor Alaknanda Samarth visited City of Desires, she expressed the idea, this work asks for a performance. In collaboration they decided to work on the production of Heiner Müller’s play Medea Material. For this Malani created a series of artworks including the multi panel painting Despoiled Shore (collection of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum), a work depicting the play’s characters alongside themes of colonialism and the Mumbai riots [4], a neon sculpture, a reverse painting, slide projection installation, and eventually directed the video documentation of the play. The venue, Max Mueller Bhavan, was located in south Bombay and had glass windows that opened the space to the street outside. Before the performance, Malani sprinkled water on the pavement outside, incorporating the reflections of neon sculpture and the four motorcycle headlights into the stage environment, effectively merging the exterior cityscape with the interior of the theater.

In 1997 Malani collaborated with theatre director Anuradha Kapur in a theatrical adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s short story The Job, which tells the story of a woman at work disguised as a man. For this she made a series of installations including the stop-motion animation Memory: Record/Erase. For the stage design, she made reverse paintings on transparent Mylar cylinders, a technique that would later develop into her large-scale installations. In her 1997 work Excavated Images, she introduced a participatory element by inviting visitors to pin safety pins into quilted pieces imbued with memories of her family’s migration from Pakistan as a collective prayer for peace.

In 1998, Malani premiered her first video installation, Remembering Toba Tek Singh, at the World Wide Video Festival in Amsterdam. This work protested India’s nuclear tests, and when it was shown in Mumbai the following year, it nearly faced closure due to its political themes but was ultimately allowed to remain on view. Although it drew negative responses from art critics, the installation attracted major public attention, with 25,000 visitors from diverse backgrounds attending over the course of ten days.

Also in 1998, Malani presented her first “shadow play” in The Sacred and the Profane, a work that questioned Hindu supremacy. She used four rotating transparent cylinders painted with imagery, projecting their shadows onto the surrounding space. This technique evolved further in her 2001 work Transgressions, where the light source was replaced with video projections accompanied by narration, giving rise to the large-scale installation format she now calls “video/shadow plays.” In these works, the rotating painted cylinders, their shadows, multiple video layers, and even the shadows of the audience interact, overlap, drift apart, vanish, and continually form unexpected relationships. This ever-changing interplay of visual elements represents the culmination of Malani’s years of experimentation, synthesizing complex themes while immersing viewers both visually and physically.

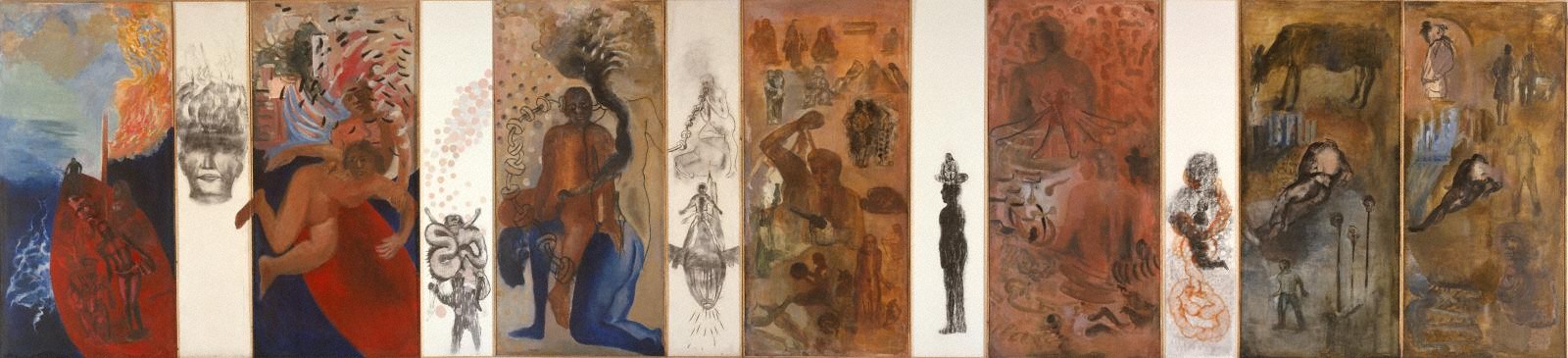

Meanwhile, Malani’s experiments using video footage of live performers took a significant step forward with Hamletmachine (1999–2000, collection of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum and others), produced during her residency at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum. This four-channel video installation, projected onto three walls and onto salt spread on the floor, brought together themes of Hindu fundamentalism, fascism, and global capitalism. The work was highly acclaimed and, as of 2013, had been exhibited at 19 venues across 14 countries.

Malani’s sustained engagement with moving images continues in recent works from 2016 onward. She creates animations by drawing on an iPad, adds her own music using apps, and presents the finished works both on Instagram and in public spaces, making use of accessible yet cutting-edge technologies and media.

Exploring the Theme of Women Through Diverse References and Quotations

If more attention were paid to the female thought perhaps we might reach something called progress. (Nalini Malani)[5]

Malani’s thematic concerns, as well as the imagery and literature she draws upon, are amazingly diverse, reflecting her vast reading and extraordinary powers of observation. Her work addresses subjects such as the tragedy of the India-Pakistan partition (1947), the violent clashes between Hindus and Muslims during the Mumbai riots (1992) and Gujarat riots (2002),[6] the Chernobyl nuclear disaster (1986), and the nuclear arms race between India and Pakistan. Her literary references span Indian culture, including mythology, the epic Ramayana, the Bhagavata Purana (hymns dedicated to the Hindu god Krishna), the 12th-century female poet Akka Mahadevi, and Pakistani writer Saadat Hasan Manto (1912–1955). European sources include Greek mythology, German playwright Heiner Müller’s (1929–1995) Medea Material and Hamletmachine, Bertolt Brecht’s (1898–1956) The Job and Mother Courage and Her Children, novelist Christa Wolf’s (1929–2011) Cassandra, and the Greek classical dramas that underpin some of these works, and so on. The visual references in her art range from traditional Indian art, the Bengali folk art of Kalighat paintings, and 19th-century Indian modern painter Raja Ravi Varma[7] to Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525/1530–1569), Spanish painter Francisco J. Goya (1746–1828), Indian architect Charles Correa (1930–2015), British author Lewis Carroll’s (1832–1898) Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky’s (1932–1986) film Stalker (1979). Japanese references include the Choju-giga (Scrolls of Frolicking Animals), Hokusai, and even absurdist gag manga from the 1990s.

Women are a consistent theme running through Malani’s diverse, multifaceted imagery, which interweaves opposing elements such as ancient and modern, East and West, high art and popular culture, and history and imagination, while often defying straightforward narrative or contextual interpretation. She particularly focuses on women who, despite their strong will and abilities, became victims of colonialism and patriarchy. Examples include Medea from Greek classical drama, who kills her own children in revenge after being betrayed by her husband and witnessing the conquest of her homeland; Cassandra of Troy, whose prophecies go unheeded; and Sita, who, after being abducted and imprisoned, is cast aside by her husband Rama when her chastity is called into question. Although Malani herself was an infant during her family’s migration after the India-Pakistan partition, her awareness that women were the primary victims of nationalism, religious fundamentalism, and the caste system – underscored by the fact that nearly 100,000 women were abducted and raped in both countries during this period – runs throughout her work.

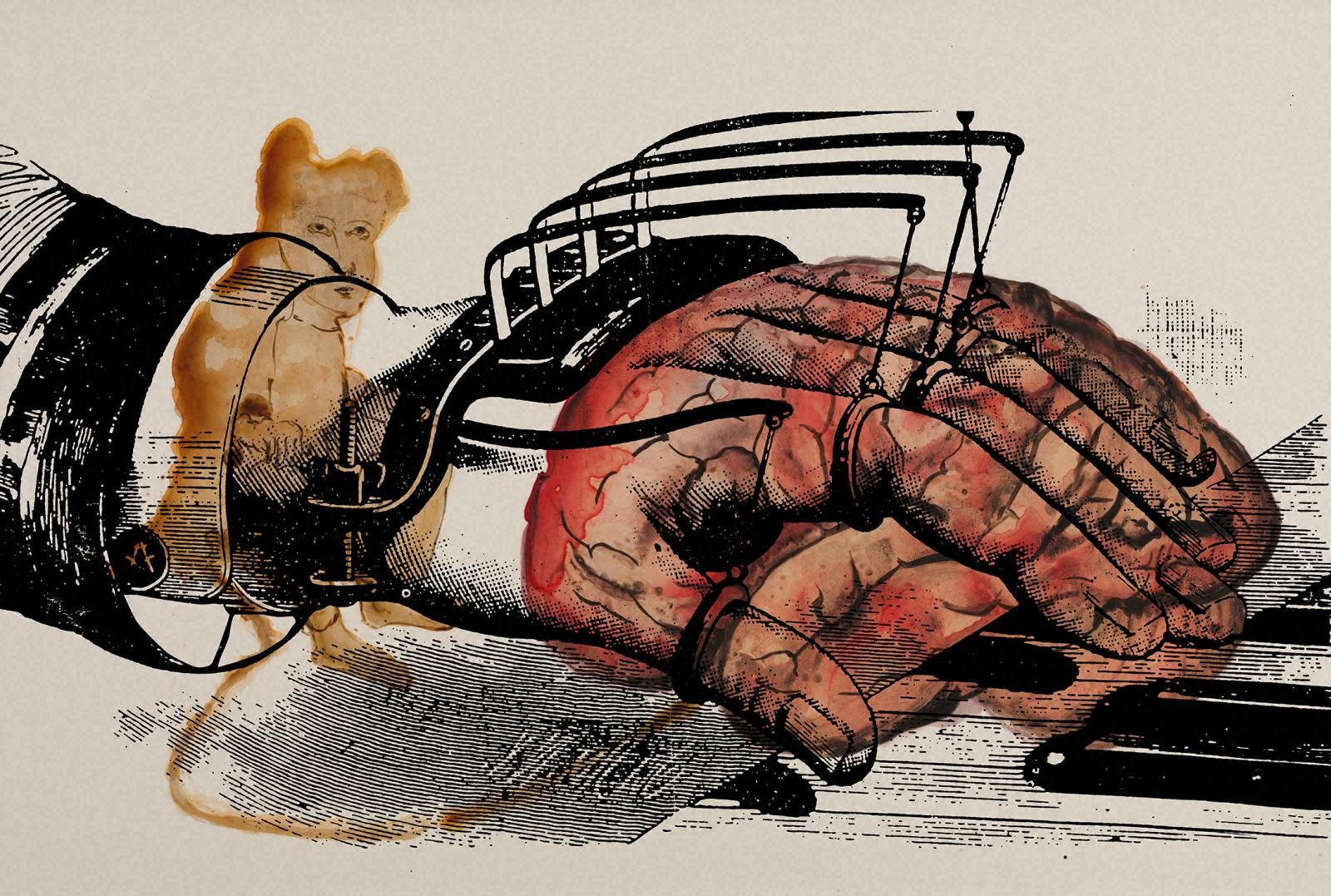

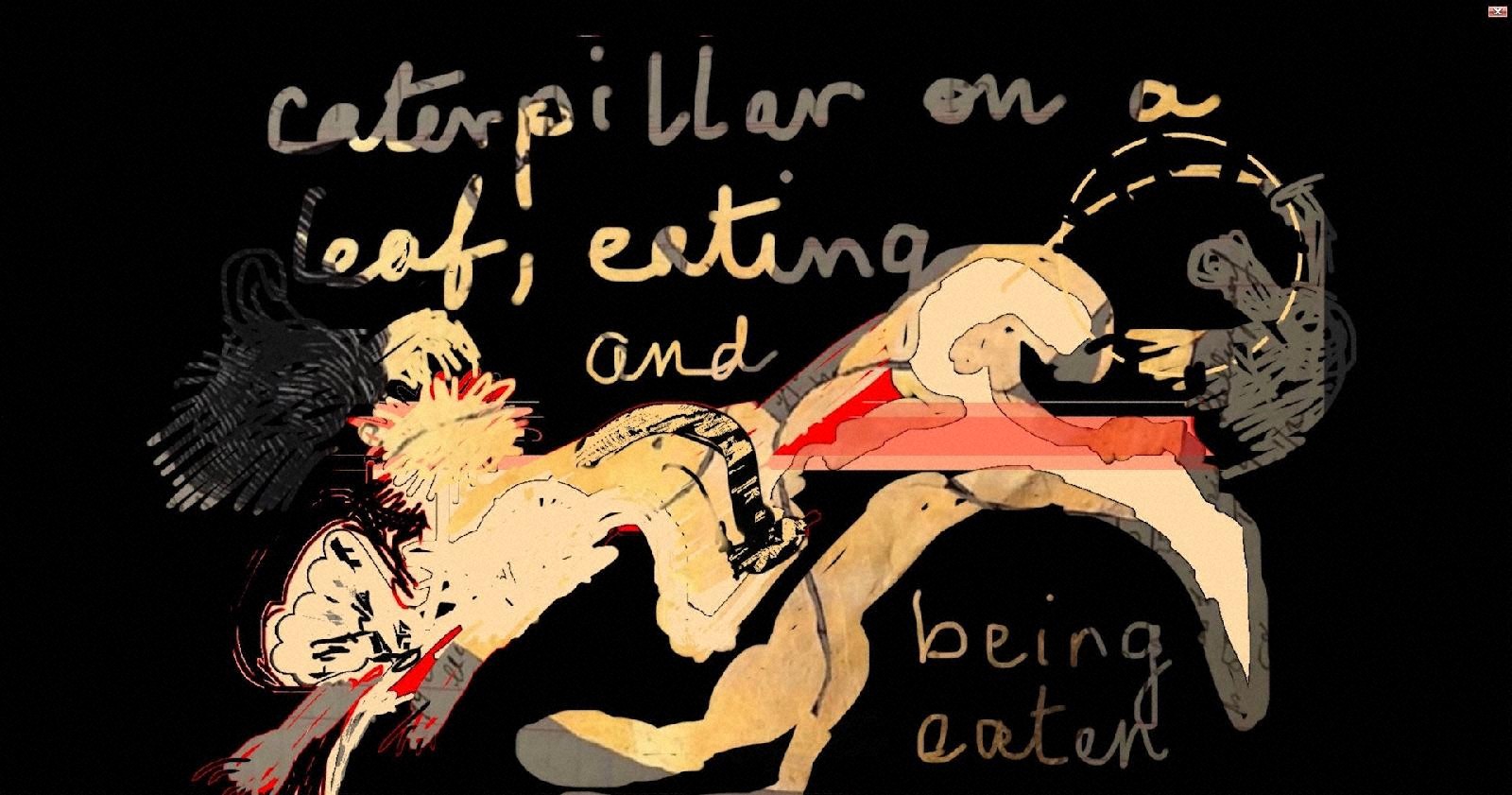

Malani approaches the theme of women not only as social beings situated within history, politics, and family, but also as biological entities. This biological perspective is evident in her video work Onanism, produced 1969 during the VIEW period (rediscovered in 2012 and since then extensively international exhibited)), which addresses female masturbation. Though suggestive, the work is pioneering in portraying female sexual desire from a woman’s perspective rather than presenting women merely as objects of male desire. Malani’s biological focus also appears in her recurring use of anatomical forms such as brains, internal organs, spinal cords, umbilical cords, fetuses, and male genitalia. This may reflect a desire to depict human life as biological existence rooted in the physical world, prior to the workings of thought or ideology. Alternatively, it may arise from her view of the body as a constant site of interaction between internal physiology and external reality. While some of these images resemble clinical illustrations from medical texts,[8] Malani often renders human figures with the fluidity of watercolor, as exemplified by her technique of painting on the reverse side of transparent sheets, drawing on the Indian tradition of glass painting. In her Mutant series, human bodies retain their form yet lose solidity and contours, appearing like shadows or ghosts. These figures signify not only the permeation of individual bodies by society, history, environment, and nature, but also their inherent vulnerability to violence.

However, the women in Malani’s works are never portrayed solely as passive victims. As seen in her 2007 work Remembering Mad Meg referencing Pieter Bruegel’s Mad Meg, Dulle Griet (1561), which depicts a woman charging into battle armed with kitchenware and household tools, Malani’s women are active agents who protest against violence, neglect, and exclusion. Similarly, the title of her 2003 work Stories Retold reflects her hope of liberating women by reconfiguring established histories and narratives, rewriting them while blending them with her own imagination.

The diverse mixture and transformation of imagery in Malani’s work can make interpretation challenging. As an accessible entry point, it may be helpful to begin with her paintings, which she has continued to produce alongside her video installations. Malani says that in Splitting the Others (2007) she brought together themes she had explored over 15 years, featuring figures such as the woman from The Job, Medea, Sita, Mother Courage, and goddesses symbolizing Mother India across 14 monumental panels. In this vast panorama, a woman advances, pulling two infants by their umbilical cords, surrounded by a sweeping landscape of imagery, nature, history, and society.

In her Kyoto Prize interview, when asked about her motivation to keep creating, Malani explained that “the themes are too big to cover in a single work.” She has also remarked, “for me a single subject matter can never be contained in one frame. So there is this obsessiveness that has to repeat the idea in different ways, even by cloning and recycling images.”[9] Even at the age of 78 (as of 2024), her drive to communicate messages to the world and to experiment with new forms of expression remains undiminished.

Relationship with Fukuoka

Malani’s connection with Japan is longstanding. She first visited the country in 1958 with her mother, who worked for an airline. Her debut in Japan came in 1969, when she participated in the 5th International Young Artists Exhibition under the name M. Nalini Jairam (Jairam being her father’s surname), showing four modernist paintings that depicted a dystopic landscape.[10]

Malani was a participant in the first Artist-in-Residence program at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum when it opened in 1999. During her residency, she produced the four-channel video installation Hamletmachine, featuring Fukuoka-based butoh dancer Harada Nobuo. A photograph of this work was later used on the cover of the catalogue and promotional banners for her retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 2017–18. Hamletmachine was donated to the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum and was shown in the solo exhibition at the Museum when Malani received the Fukuoka Prize for Arts and Culture in 2013. In addition to another residency work, the stop-motion animation Stains (1999–2000), she gifted the museum with a series of seven prints titled Cassandra’s Gift (2009) upon receiving the Fukuoka Prize, and the digital video Life (2023) following her Kyoto Prize award.

These donations are a testament to how highly Malani regards not only the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum’s residency program but also its broader activities. In her essay for the catalogue of the 4th Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale 2009, she wrote:

Also it [Fukuoka Asian Art Museum] has forged connections between Asian artists which have had a profound influence on their art making. It was at FAAM that a number of Asian artists started their careers 10 years ago and today they are important in the international art world. I cannot any more imagine Asian art without FAAM. (4th Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale 2009 exhibition catalogue, p. 195)

(Kuroda Raiji, translated by Christopher Stephens)

[1] Nalini Malani, Stories Retold, New York: Bose Pacia Gallery, 2004, 1.

[2] For an essay by Fukuoka Asian Art Museum curator Rawanchaikul Toshiko, who visited this studio, see the museum’s blog: “Munbai no uradori” (Tenjichu no Nalini Malani Ryakudatusareta kishibe ni yosete) [Mumbai’s Back Streets (On Nalini Malani’s Despoiled Shore, Now on View)]: https://faamajibi.blogspot.com/2023/11/blog-post.html

[3] A city in northwestern Rajasthan state with its own tradition of miniature painting. In the 19th century, it was influenced by Western painting.

[4] In December 1992 and January 1993, violent clashes between Hindus and Muslims occurred in Mumbai, triggered by the destruction of a mosque in Ayodhya by Hindus. The majority of the nearly 900 victims were Muslims, as the violence was instigated by far-right Hindu fundamentalist groups.

[5] Robert Storr, Nalini Malani (Mikan, 2008), n.p. This is a significant quote also cited at the beginning of the retrospective exhibition catalog at Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (New Delhi): Nalini Malani: You Can’t Keep Acid in a Paper Bag 1969–2014, Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (New Delhi, 2014).

[6] In February 2002 in Gujarat state, many Hindus, including pilgrims, died in a train fire. Hindu fundamentalist groups blamed pro-Pakistan Muslims for this and retaliated by attacking numerous Muslims and raping women. The majority of the over 1,000 victims in the riots, which continued for three months, were Muslims.

[7] The video in the installation Unity in Diversity (2003)

exhibited at Crossing Visions II Indian Video Art: History in Motion

(Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, 2004) used Varma’s oil painting Galaxy of Musicians (1893).

[8] Malani had been interested in biology since high school, and says she used the pretext that she would earn a living by drawing medical illustrations to secure her father’s permission to attend art college.

[9] Thomas McEvilley, “Locating the Female Gaze,” Nalini Malani, Milan: Edizioni Charta, 2007, 19. The source is listed as Kamala Kapoor, “Missives from the Streets,” Art and Asia Pacific, Vol. 2. No. 1 (1995), 42, but it cannot be located, so there may be another source.

[10] Other Indian exhibitors were Anandmohan Naik, Barwe Prabhaka, and Darshan. The institution making selections on the Indian side is unknown. Exhibitors from Japan included Hara Takeshi, Kato Akira, Kimura Kosuke, Haraguchi Noriyuki, Kashihara Etsutomu, Anzai Shigeo, and Fukuda Katsubon.