Park Seobo

Distinctively Korean Abstract Painting: Blissful Spaces Where Handcraft and Materials Converge

- Name(Chinese letter)

- 朴栖甫

- Name

- Park Seobo

- Media

- Painting

- Region

- South Korea

- Year of Birth

- 1931

- Place of Birth

- Yecheon, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea

- Year of Death

- 2023

- Place of Death

- Seoul, South Korまる

- External Link

- Link to Art Terms

- Link to Regions

-

Plate of artwork

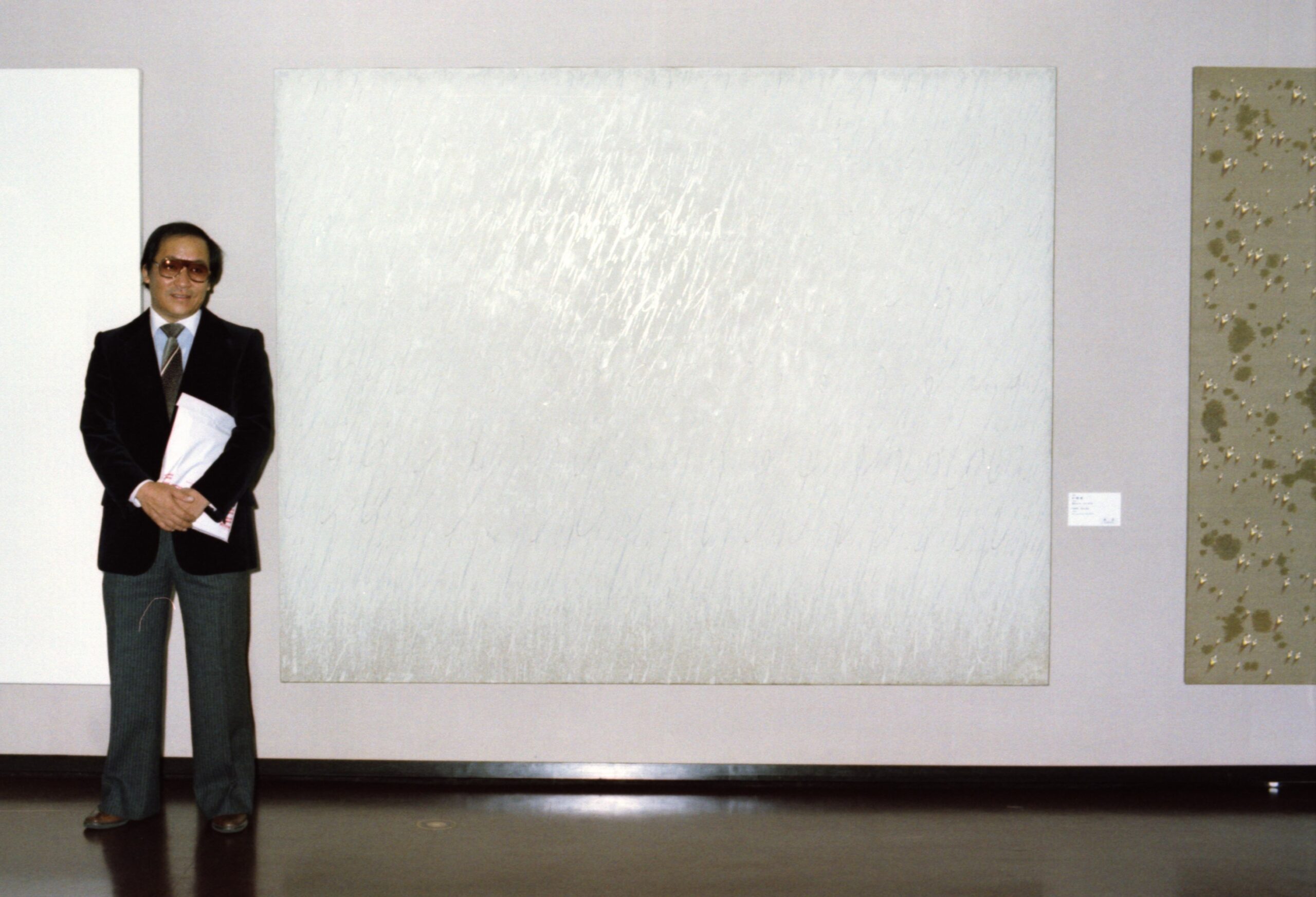

Park standing beside his work in Contemporary Asian Art Show, Fukuoka Art Museum, 1980.

Waterdrops by Kim Tschang-yeul, Park’s friend, is in the right.

Park (first from the righ, front row) visits the studio of Adachi Jo (4th from the left, back row), painter, during the Contemporary Asian Art Show, Fukuoka, 1980.

●The Father of Monochrome Painting

Park Seobo is not only known as “the patriarch of Korean Monochrome Painting” and “a pioneer of the Korean avant-garde,” but also stands out as an artist whose artistic accomplishments are unparalleled within the broader vantage point of “the modern painting of Asian countries” that “has developed in different context from that of Europe and America.”[1]

Until the 1980s, Korean Monochrome Painting was the only form of Asian contemporary art that was both consistently presented in Japan and actively noted by art critics of the time. Today (2025), Korean art has at last gained international recognition for installations and video works as well. In addition to Monochrome Painting, other movements have been increasingly researched and showcased in the West, including Minjung Art (People’s Art) from the 1980s and 1990s, which began to be featured in national museums after South Korea’s democratization, as well as experimental art from the 1960s and 1970s by artists such as Kim Kulim, Action Art (performance) by artists such as Lee Kun-yong, and earthworks by artists such as Lee Seungtaek.[2] Despite this diversity, Monochrome Painting remains perhaps the only abstract painting style in all of Asia that can claim to be fully distinct from Western art while achieving artistic maturity Much Asian abstract art, lacking the means to assert its originality and uniqueness without relying on exotic themes, traditional artistic styles (such as Indian Tantric art),[3] or region-specific materials, is often readily dismissed as merely an imitation of Western art.

Park Seobo’s most refined painting style is represented entirely by his long-running Écriture[4] series. While his works from the early period (1973–84) and later period (1984–2023)[5] differ in terms of form and material, they comprise a cohesive body of work. However, it was a long journey before Écriture could reach a state of bliss that transcended real-world tragedies and suffering. According to the critic Seo Seongrok, this was not only a personal history of continuous formal experimentation or efforts to establish a position in the art world, but also a history shaped by the experience of the “June 25 Generation”—those who were profoundly affected by the outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, 1950. Unlike the previous generation, many of whom studied in Japan, this generation lived through ground warfare throughout Korea in their youth. Experiencing the devastation of countless deaths, acts of violence, and the destruction of culture and civilization led them to fundamentally question the established values that had caused such devastation.

●The Anti-National Art Exhibition and Art Informel Painting

Park Seobo (birth name Park Jaehong) was born into a well-to-do family. His father worked at an office that drafted legal documents, a role similar to that of an administrative scrivener in present-day Japan. Despite his father’s wishes for him to become a lawyer, he pursued his ambition to be a painter and studied East Asian painting in the Art Department of the Faculty of Literature at Hong-ik University. However, soon after entering university, he was faced with the outbreak of the Korean War and suffered further hardship when his father died of illness.[6] During the war, he was taken by North Korean troops who had advanced into Seoul and was forced to create stage sets for propaganda plays. Fortunately, after the South Korean army’s counteroffensive, he was not accused of being a northern collaborator, and he temporarily worked for the US military.[7] In 1952, he re-enrolled at Hong-ik University’s wartime school, which had been newly established in Busan. As there was no professor of East Asian painting, he encountered Kim Whanki, one of the founders of Korean modernist painting, and changed his major to Western painting.

After the war, he returned to Seoul, graduated in 1954, and in 1956, ran the Ankuk-dong Art Research Center, Korea’s only art research institute at the time, established by painter Lee Bongsang. At that time, Korea regularly held the National Art Exhibition (Kukjeon), which inherited the structure and networks of the Chosun Art Exhibition (Sunjeon) from the Japanese colonial period, and Park exhibited there in 1954 and 1955. However, in June 1956, during a four-person exhibition with university friends, he released an Anti-National Art Exhibition declaration, a crucial moment in Korean art history that shocked the art world. The following year, he participated in the second exhibition (commonly known as the Hyundai Exhibition) of Korea’s first avant-garde art group, the Modern Artists Association, led by Kim Tschang-yeul and others, and continued to show work with the group until the sixth exhibition in 1960. The third Hyundai Exhibition, held at Hwashin Department Store in Seoul in 1958, is particularly noted in art history as the starting point of Art Informel painting in Korea. However, few works from this period have survived.[8]

In 1961, Park was invited to Jeunes Peintres du Monde à Paris,[9] organized by the Comité Français of the International Association of Art[10] under UNESCO, where he won first prize at the exhibition for Péché Originel. After returning to Korea, he held his first solo exhibition in October 1962 at the National Library, presenting his Primordialis series. This series, which continued until the mid-1960s, contained no discernible figurative forms, yet unlike pure abstraction, its dark tones and strange shapes resembling skeletal structures and internal organs led to its being described as “X-ray painting.” These works created a strong impression distinct from French and Japanese Art Informel, evidently reflecting the trauma of his wartime experiences.

In the late 1960s, in contrast to Primordialis, he shifted to the Hereditarius series, incorporating the traditional Korean “five directional colors” (black, yellow, blue, red, and white) and geometric forms. He also adopted airbrush techniques, which were popular at the time, in figurative paintings of empty clothing that symbolized human absence. Park’s works from this period were markedly disconnected from both his earlier expressive Art Informel and dark Primordialis series, and from his later, more refined Écriture series. These works should be considered transitional, as he experimented with styles popular in the West and Japan, including hard-edge abstraction, Pop Art, and Op Art.

●Development of Écriture 1: Early Period (1973–1984)

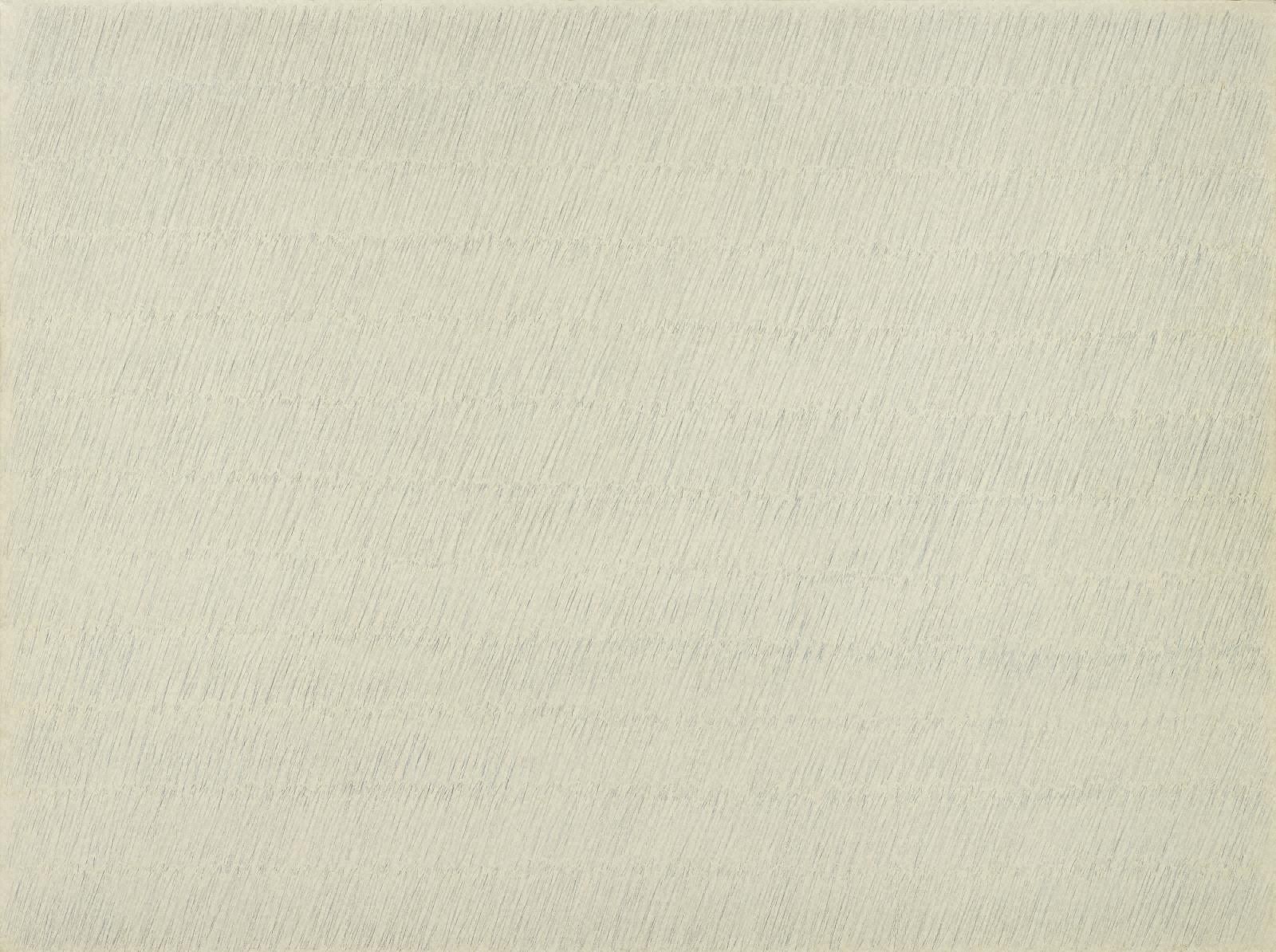

Pencil and white paint are not materials for painting pictures, but tools to empty “myself,” and for self-discipline.[11]

Although he had already begun experimenting with Écriture, the series that would become his signature work, as early as 1967, it was first exhibited in his solo exhibitions at Muramatsu Gallery (Tokyo) and Myeong-dong (Seoul) in 1973. Early Écriture works involved applying white paint to canvas and, while it was still wet, moving a pencil back and forth at regular intervals to make lines. He then applied another layer of white paint and repeated the process of drawing lines, eventually covering the entire surface with nearly uniform patterns and textures. The inspiration for this technique came from watching his three-year-old second son attempting to write characters in the grid squares of his older brother’s elementary school language notebook. Unable to fit the characters properly, he scribbled over them to cover the mistakes.[12] As this anecdote suggests, in the early Écriture series, the artist’s act of drawing lines with a pencil was less about creating forms on a surface and more like an act of erasing. At first glance, the lines may resemble childlike scribbling, yet each action – maintaining a consistent width, controlling the paint’s thickness and fluidity, and fitting everything within the picture plane – required the same level of concentration as calligraphy, as well as rigorous planning to structure the surface. Regarding Écriture works exhibited in 1978, the art critic Nakahara Yusuke aptly described the tension in Park’s work between drawing (making lines) and painting (applying paint): “The drawn lines awaken the oil paint, and the paint gives vitality to the lines.”[13] The resulting surface, though spread uniformly without figurative forms or even a composition, achieves a harmony between the rhythm of the handcraft and the materiality of the paint, guiding the viewer’s gaze while enfolding them in a pleasant, quasi-physical embrace.

According to the art critic Oh Kwangsu, the colors and textures of Écriture evoke the aesthetics of Goryeo celadon, buncheong ware, and Joseon white porcelain. In particular, the engraved-line effect, appearing as if scratched into milky-white paint, recalls incised patterns in the glazes of Korean ceramics. However, rather than reviving traditional aesthetics to appeal to foreign audiences or antique enthusiasts, Écriture emerged as an experiment in redefining painting as a means of self-cultivation and self-discipline by relinquishing active agency over “drawing,” “painting,” or “creating” (arguably a modernist mindset).

●Development of Écriture 2: Later Period (1984–2023)

From 1984 onward, the Écriture series retained the same title but differed completely in terms of both materials and production methods. The process was as follows:

First, I leave paper in water for over a month. When that is done, I layer three sheets of paper and, using thick pencil lead, draw horizontal lines across them all day long in a meditative state. Occasionally, air gets trapped between these three sheets of paper. But if I continue for 14 or 15 hours, the air naturally escapes.[14]

The most evident difference from the early period was that, instead of linen, the works were executed on hanji, traditional Korean paper made from paper mulberry. For Koreans, paper is not merely a material but an integral part of the national culture, familiar through changhoji window screens, wallpaper, and floor paper changpanji placed on ondol (heated floors) in traditional homes. In this cultural context, when Park participated in the International Paper Conference in Kyoto in 1983, he noted that Western artists such as Robert Rauschenberg lacked respect for paper as a material. He argued that his works should not be categorized as “mixed media on paper” but rather as made “with paper,” emphasizing that his actions and the material itself were inseparable. While Park’s adoption of hanji marked a return to traditional Korean materials and a departure from Western art, it also reflected a shift in his approach. Unlike the early Écriture, where traces of the artist’s agency remained, the later works transcended subjectivity through reverence for the material.

Initially, these works showed fine, multi-directional movements, but over time they evolved into compositions full of tension, structured around dark tones and vertical geometric patterns which, while static, retained a raw material presence. It was no longer about “drawing,” but about leaving vestiges of movement on paper.[15] Whereas in the early period, paint and pencil lines remained on the canvas surface, in the later period, both line and color permeated and became one with the paper. The coexistence of line drawing and painting that had defined the early Écriture disappeared, and action and material became inseparable.

Remarkably, at this stage, bright colors such as red, pink, light blue, and yellow emerged in place of the austere white and dark tones of his earlier works. However, rather than disrupting the structure or material presence of the surface, these colors imparted a sense of heavenly bliss. This was the state of serenity that Park Seobo reached after years of struggle and self-discipline.

●Organizational Activities

What stands out in Park’s career is that, while steadfastly pursuing his own unique artistic investigation and standards of perfectionism, he also dedicated himself to establishing avant-garde art completely separate from colonial-era influences, organizing Korea’s contemporary art scene, and promoting international recognition of Korean art in the West and Japan. Alongside his artistic practice, he taught at the Hong-ik University College of Fine Arts from 1962 to 1997 (except for 1967–69).

During his stay in France, he took the lead in negotiations, working with critic Lee Yil and others to secure Korean participation in the 2nd Biennale de Paris (1961) and introduce Korean art to the international scene, but despite his determined efforts, he was ultimately unable to exhibit his own work, to his great disappointment.[16] However, he later participated in the 3rd Biennale de Paris (1963) and served as commissioner for the 4th Biennale (1965). In 1969, he was involved in planning and presenting a Korean art exhibition at a gallery in Manila, Philippines. A European touring exhibition was planned for September 1979, but never materialized due to the political turmoil following the assassination of President Park Chunghee on October 26. In 1980, after losing the election for chairman of the Korea Fine Arts Association, he focused primarily on his art practice. However, as will be discussed later, he played a central role in organizing Korean works in the Contemporary Asian Art Show at the Fukuoka Art Museum that same year.

In Korea, starting in 1972, he helped foster emerging artists through the Independent Exhibition, a non-juried show that originated in France and was also held in Japan. He joined the Korea Fine Arts Association in 1970, serving as its vice chairman, and subsequently chairman from 1977 to 1980. From 1973 onward, he organized the Seoul Contemporary Art Festival, and to promote contemporary art outside the capital, he also arranged exhibitions in Daegu, Busan, and Gwangju.

A particularly important initiative in relation to both Park’s artistic vision and his institution-building efforts was the École de Séoul exhibition, which ran for 25 years starting in 1975. Leading the project, Park aimed to establish an internationally competitive art movement independent of American influence. However, from 1977 onward, Monochrome Painting became the dominant style and the number of similar-looking works increased, thus the exhibition seemed to exclude diverse artistic experiments.

In 2019, following his first retrospective in 1991, Park held his second retrospective at the National Museum of Contemporary Art and established the Gizi Foundation (renamed the Park Seobo Foundation in 2023) to support younger generations of artists. The foundation’s website, which remains active following his passing in 2023, is a comprehensive resource offering extensive access to archival materials on Park’s work and legacy.

●Relationship with Japan and Fukuoka

In 1965, Japan and Korea signed the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea and restored diplomatic relations. Park subsequently participated in the Contemporary Korean Painting exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art in 1968, marking his work’s debut in Japan. During his first visit to Japan, he met Lee Ufan, a Korean-born artist who had established himself in the Japanese art world through works and theoretical writings in the Mono-ha movement, and the two developed a long-lasting friendship. The following year, Park exhibited in the 5th International Young Artists Exhibition: Asia / Japan at the Seibu Department Store in Ikebukuro. At Expo ’70 Osaka, he presented a three-dimensional work that evolved out of Hereditarius in the Korean Pavilion, designed by architect Kim Swoogeun.[17] However, the work was removed after being deemed anti-government.

Through these experiences, Park, who was proficient in Japanese, became even more active in Japan. This led to his first solo exhibition in the country at Muramatsu Gallery in 1973. Through cooperation among Japan-based Lee Ufan, the aforementioned Nakahara Yusuke (one of postwar Japan’s leading art critics), and Korea-based Park Seobo, the ongoing presentation at Tokyo Gallery of Korean paintings later termed Monochrome Painting was secured. A landmark in this endeavor was the historically significant Five Hinsek “White”: Five Korean Artists exhibition in 1975.[18] Nakahara also contributed a text to the pamphlet for Park’s solo exhibition at Tokyo Gallery in 1978.

For the first Contemporary Asian Art Show at the Fukuoka Art Museum, an exhibition that was the precursor of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Park participated in a preparatory conference in June 1980.[19] By this time, he had already visited Japan more than 30 times.[20] Although he had lost the election for chairman of the Korea Fine Arts Association, he represented Korea at the conference in the capacity of “former chairman of the Korea Fine Arts Association.”[21] Furthermore, the fact that his home was designated as the collection point for Korean works further demonstrated that, even after stepping down as chairman, he remained highly influential as the de facto coordinator for the Fukuoka Art Museum’s Asian art exhibition. It is no surprise that many of the selected artists were participants in École de Séoul, the group he led.[22]

●Transcending the Self

Following the “Monochrome Painting fever” that gained momentum after the works appeared at the 2015 Venice Biennale, the abstract paintings of Park Seobo and his contemporaries have seen their values rise even higher in the international art market. However, as touched on earlier, there is a risk that these works may be overly stereotyped as inherently “East Asian” or “Korean,” particularly in light their aesthetic resemblance to traditional Korean ceramics. Indeed, Park’s longest-running and best-known series, Écriture, reflects an artistic sensibility that rejects the modern Western notion of the subject, and by extension the associated concepts of expression and representation, in favor of a sense of unity with nature. This reflects an “East Asian” sensibility in alignment with Lee Ufan’s Mono-ha explorations in both theory and practice, which involved minimal intervention in the arrangement of natural materials. Given their long friendship, mutual influence between the two is possible. However, what fundamentally distinguishes Écriture from Mono-ha is that, while the former may appear to be the result of simple, repetitive, anti-intellectual labor, it was in fact guided by an extraordinary level of intelligent control. Every element, from the movements of the hand to the handling of materials and the composition of the picture plane, was precisely calculated to produce a meticulous and refined surface.

Unlike his close friend the painter Kim Tschang-yeul, known for his Waterdrops series, who with his unkempt hair and beard had an ascetic, otherworldly presence akin to a hermit, Park’s appearance was neither stereotypically “artistic” nor quintessentially “East Asian.” With sharply defined features that conveyed a strong will, neatly combed and styled hair, and a suit, he often looked more like a businessman or politician than a painter. It cannot be denied that his excessive confidence, natural leadership, and perfectionism frequently led to friction with other artists, as was evident in both the Hyundai Exhibition and the Korea Fine Arts Association. Artists associated with Minjung Art, who fiercely resisted the dictatorial regimes of Park Chunghee and Chun Doohwan, criticized him as a power-driven establishment figure.[23]

Park Seobo heralded the emergence of avant-garde art in Korea by defying the conservative National Exhibition, a remnant of Japanese colonial rule, and his contributions to Korean art through education, exhibition planning, and international outreach were immense, while in his later years he achieved lasting recognition both at home and abroad. However, his journey was far from smooth and was marked by hardships: the loss of his father, near-death experiences during the Korean War, extreme poverty, the destruction of his works in war and fire, failed exhibition plans, and conflicts within the art community. It was not despite, but because of these struggles that Écriture emerged, not merely as an artistic practice but as a process of spiritual purification for both creator and viewer. When surveying the entire history of contemporary Asian art, his lifelong exploration and singular vision stand out as truly exceptional.

(Kuroda Raiji, translated by Christopher Stephens)

Selected Bibliography

Seobo Arts and Cultural Foundation (ed.), Park, Seo-bo, Seoul: Seobo Arts and Cultural Foundation, 1994.

Seo Seongrok, Jaewon misulchakkaron 8: Park Seobo. Engporeumeleseo tansaekhwakaji [Jaewon Artist Study 8: Park Seobo (From Art Informel to Monochrome Painting], Seoul: Jaewon, 2000.

Seobo Art Foundation Planning, Park Seobo: Écriture 1994-2001, Seoul: Jaewon, 2001.

Kate Lim, Park Seo-Bo: from Avant-Garde to Ecriture, Singapore: BooksActually, 2014.

Empty the Mind: The Art of Park Seo-Bo, Tokyo: Tokyo Gallery + BTAP, 2016.

Park Seobo Foundation website: https://parkseobofoundation.org/

NOTES

[1] Minemura Toshiaki’s essay “Interruption and Concealment” was featured in the catalogue for the Park Seobo exhibition (Tokyo Gallery, 1994). Originally written in 1991, it first appeared in exhibition catalogues of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea and Duson Gallery that year. Reprinted in Park, Seo-bo (1994), The author later retitled it “The Whole That Should Be Concealed.”

[2] For further reading, refer to the catalogue of the American touring exhibition Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, Kyung An and Kang Soojung, eds., New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2023.

[3] Paintings and sculptures based on abstract Hindu diagrams (tantra) and other sources developed amid the mid-1960s trend of returning to tradition. Examples include works by Santosh and Biren De.

[4] The Korean word translated as Écriture corresponds to 描法 (Myobeop), using the same kanji characters as in Japanese. For international audiences, the French word Écriture, derived from the title of Roland Barthes’s book Writing Degree Zero (Le Degré zéro de l’écriture), is used. The word originally refers to the act of writing, handwriting, writing style, or written text.

[5] According to Oh Kwang-su, the early period of Écriture can be subdivided into 1973–76 and 1976–84, and the later period into May 1984–1994 and 1995–99. See Oh Kwang-su, “Stages of Écriture: On Park Seobo’s Écriture Series,” in Park Seobo: Écriture 1994–2001, Jaewon, 2001.

[6] After his father’s death, Park’s mother supported the family by making and selling medical plasters and providing health consultations, which had been her family’s business.

[7] After the war, Park underwent training at the Army Infantry School.

[8] Park was once shocked to discover that his own paintings, which he had abandoned due to lack of storage space when moving, had been repurposed as roofing for barracks.

[9] Upon arriving in Paris, Park learned that the conference had been postponed. He was forced to live in extreme poverty in Paris for 10 months until he received prize money from the exhibition.

[10] The International Association of Art (IAA) subsequently played a major role in the genesis of the Asian art exhibition at Fukuoka Art Museum.

[11] Park Seobo, “Fragmentary Notes,” Gallery, autumn 1981, quoted in Seo Seongrok, Park Seobo (From Art Informel to Monochrome Painting), Jaewon, 2000, p. 68.

[12] The following videos include a reenactment of this scene:

KBS production “How Park Seobo’s Écriture Began” (Korean only):

EBS production, provided by the Gizi Foundation, “Park Seobo’s Life and Art” (with English subtitles):

[13] Nakahara Yusuke, essay in Park Seobo exhibition pamphlet (Tokyo Gallery, 1978).

[14] Anonymous, “Artist No. 4: Park, Seo-Bo,” Gekkan Gallery, January 2006, pp. 50–56.

[15] Oh Kwang-su suggests that the later Écriture series is also reminiscent of pottery from the Silla and Proto-Three Kingdoms period (1st century BCE – 4th century CE).

[16] Korean artists exhibiting at the Biennale de Paris included Kim Tschang-yeul, Chang Seongsun, Chung Changsup, and Cho Yong-ik. The commissioner was Kim Byeong-gi. It is unclear whether Park Seobo’s exclusion was due to Kim Whanki, who reportedly disliked him.

[17] For information on the Korean Pavilion at Expo ’70 Osaka, see Kuroda Raiji, “Ouchi de shiritai Ajia no ato 13, Tokyo Orinpikku to Osaka Banpaku no Ryu Kyonche, Ajia bijutsu no kokusaika no hajimari” [Learn About Asian Art at Home, Vol. 13: Ryu Kyungchai at the Tokyo Olympics and Expo ’70 Osaka – Dawn of the Internationalization of Asian Art], on the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum’s official blog Ajibi na hibi [FAAM Days], December 3, 2021:

[18] Monochrome painters, besides Park Seobo, who held solo exhibitions at Tokyo Gallery included Lee Ufan, Kim Tschang-yeul, Yun Hyongkeun, and Chung Changsup. Other Korean artists included Kim Ikyong, Shim Moonseup, Lee Kanso, and Lee Myungmi.

[19] Park visited Fukuoka again in November for the opening as the person responsible for unpacking, and attended the opening ceremony together with art critic Lee Il, who was a symposium participant.

[20] “Ajia kara no yujin, Kankoku, Paku Zaiko san” [A Friend from Asia: South Korea, Park Jaehong], Nishinippon Shimbun, November 13, 1980.

[21] At the opening, Park’s titles were listed as “Former Chairman of the Korea Fine Arts Association (IAA Korea Committee Director), Former Vice President of Federation of Artistic and Cultural Organization of Korea http://yechong.net/ Current Advisor to the Korea Fine Arts Association, Current École de Séoul Steering Committee Member.”

[22] The artist profiles submitted for the catalogue indicate that 23 out of 27 artists had exhibited with École de Séoul.

[23] The Park Seobo Prize was established during the 2022 Gwangju Biennale, but faced protests claiming that a prize named after an artist who had aligned himself with the dictatorship was inappropriate for Gwangju, a sacred site of the democratization movement. The prize was canceled after just one iteration. https://namu.wiki/w/박서보