Heri Dono

Satirizing Social Absurdities Through Cross-Genre Cultural Synthesis: A Pioneer in the Internationalization of Asian Art

- Name

- Heri Dono

- Media

- Painting, Sculpture, Installation, Performance

- Region

- Indonesia

- Year of Birth

- 1960

- Place of Birth

- Jakarta, Indonesia

- Place of Residence

- Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Link to Art Terms

-

- Link to Regions

-

Path to International Recognition

Heri Dono is one of the most widely and actively engaged Asian artists on the international stage, with his participation in international exhibitions only exceeded by Cai Guoqiang and Yang Fudong.[1] In 2011 alone, he held two solo exhibitions and participated in 22 group shows in different parts of the world.[2] This is due not only to his endless ideas and prolific output, but also to the way his work captivates general audiences with its humorous and distinctly Indonesian forms. His art has such strong international appeal because, while deeply rooted in Indonesia’s unique culture, it possesses an innovative quality that transcends regional boundaries, shaping a new era of Asian art.

Born in Jakarta, Heri Dono (birth name Heri Wardono) was accepted by the Bandung Institute of Technology, but he chose to pursue his education at Indonesian College of Fine Arts in 1980 until he withdrew of his own accord in 1987. (Indonesian College of Fine Arts, Sekolah Tinggi Seni Rupa Indonesia [STSRI] is former Indonesian Institute of the Arts, Yogyakarta [Akademi Seni Rupa Indonesia, ASRI], presently Indonesian Institute of the Arts Yogyakarta [Institut Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta, ISI Yogyakarta]). A crucial stage of his artistic development was his apprenticeship with Sukasman, a master puppeteer (dalang) of traditional wayang kulit shadow puppetry, from 1987 to 1988. Sukasman was not a conventional dalang; he studied advertising at ASRI and transformed traditional flat puppets into more realistic, thus created Gagrak Anyar, a modernized interpretation of traditional classical wayang, that saw him criticized and excluded from the conservative puppetry community.[3] Traditionally, wayang kulit served to teach moral lessons through epic tales such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata, while also functioning as a medium for satirical critiques of contemporary political and social issues. Later he worked as a graphic designer in the US and the Netherlands. Sukasman’s approach to contemporizing traditional performing arts would later play a central role in Heri Dono’s rise to prominence.

His early paintings had a narrative quality, featuring intricately colored, biomorphic forms, reminiscent of Miró or Kandinsky, seemingly conversing with one another. Later, flat-faced characters with two front-facing eyes reminiscent of the Wayang Beber tradition became central to his work, and he continued painting them even after expanding into other media such as installation. In compositions on a single, depthless plane, where paired characters engage in dialogue, conflict, or mockery as in a scene from a play, Heri Dono embedded current political allegories based on actual politicians, political parties, and military figures recognizable to Indonesian viewers at the time. For example, Talking of Nothing (1991, collection of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum) depicts two military figures, indicated by their boots and rank insignia, and references the Santa Cruz massacre in Dili, East Timor.[4] Under Suharto’s dictatorship, with news reports censored and freedom of speech nonexistent, ordinary people, relying on uncertain information, were powerless to protest and could only engage in futile discussions. This is represented by the people facing each other inside the mouth of the left-hand soldier. Meanwhile, one soldier points a gun at himself, while the other has only one leg, implying that they, too, are victims of an absurd society.

In Talking of Nothing and many of Heri Dono’s other works, characters typically have dangling male genitalia. In his three-dimensional works, winged angels are also depicted as male (though there are some female angels as well). This may reflect a society where both power and salvation are monopolized by men, but the exposed and undersized genitals of these pathetic characters emphasize a sense of ridicule. Wayang kulit and comics, both of which embrace boundless imagination and absurd creativity, serve as ideal weapons to expose the hidden irrationalities of Indonesian society such as abuse of political power, conflict, corruption, and the empty rhetoric of politicians and mass media.[5]

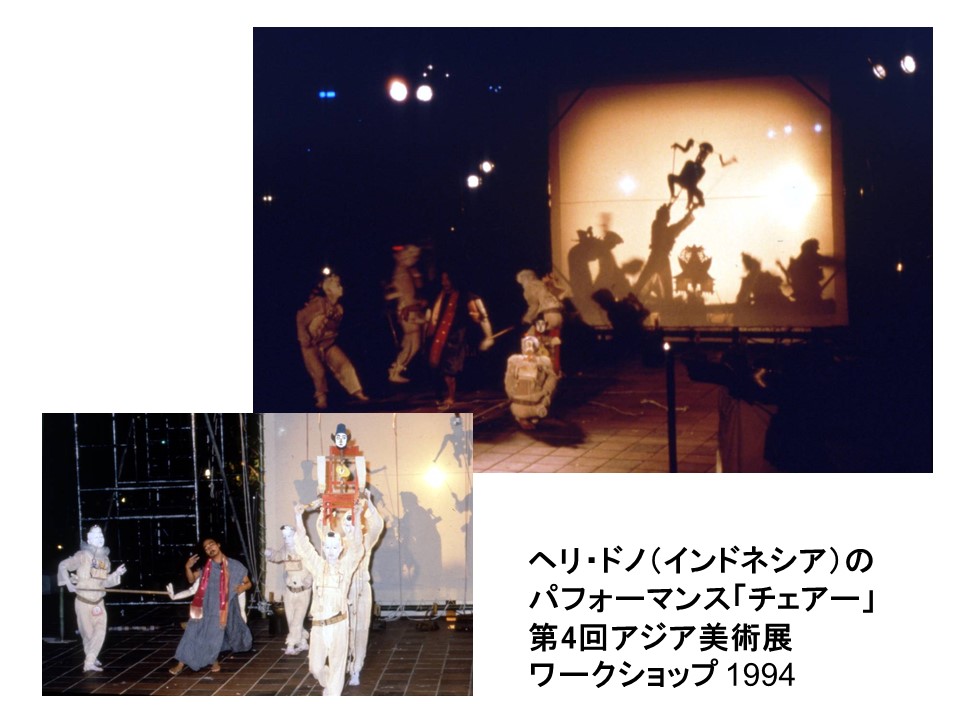

Installations That Breathe Life into Objects

However, while Dono’s paintings had a strong impact as standalone works, his ongoing international recognition would not have been possible without his expansion into installation and performance. In New Art from Southeast Asia 1992, a major exhibition that played a decisive role in establishing contemporary Southeast Asian art in Japan, in addition to paintings and small three-dimensional works[6], he reinterpreted the wayang kulit performance format in the installation Shadow Puppet Story. The following year, in 1993, he performed Chair in Canberra, Australia. He later participated in the 1996 Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art in Brisbane and took part in a group exhibition in Amsterdam, gradually establishing himself on the international stage. In 1994 he exhibited at the 4th Asian Art Exhibition, which traveled from the Fukuoka Art Museum to the Setagaya Art Museum in Tokyo and other venues, presenting groundbreaking works that redefined perceptions of Asian art, gaining his first nationwide recognition in Japan. During a residency in Fukuoka, he re-performed Chair, further expanding his audience. After these exhibitions in Australia and Japan, his international reputation grew, and he became a regular participant in major international exhibitions in Gwangju, Yokohama, Sydney, São Paulo, and elsewhere.

Among the major works that emerged along Heri Dono’s path to international stardom were installations such as Gamelan of Rumor (1992–93, collection of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum),[7] his first work to incorporate electric mechanisms, and Fermentation of the Mind (1994, collection of M+), along with the performance Chair. Gamelan of Rumor features 27 of the traditional instruments, with electric-powered wooden mallets fixed in place to strike metal plates, accompanied by recordings of Javanese songs and Japanese biwa music.[8] The randomly produced sounds, which can hardly be called music, are somehow nostalgia-inducing. However, far from evoking warm ethnic sentiments, the absence of human performers makes the orchestra an eerie one. Fermentation of the Mind consists of ten sculpted figures with heads modeled after the artist’s own, sitting at classroom desks and continuously nodding through electrical mechanisms. This imagery, suggesting a passive acceptance of authority, whether in education or governance, is equally unsettling.

In Gamelan of Rumor, “objects” autonomously play music as if imbued with life, while in Fermentation of the Mind, living people are reduced to mechanically operated “objects.” This mutual exchange between humans and objects extends beyond political satire, reflecting an animistic worldview in which people, animals, imaginary beings (gods, angels, demons, ogres, animation and comic-book characters), and inanimate objects all equally possess life or spirit. This animistic perspective rejects the notion of the privileged human subject (or artist) as the one who controls and assigns meaning to matter and nature. As one interpretation has it, “For him [Heri Dono], objects are also subjects, and vice versa—an impossibility in Western thought.”[9] In other words, his perspective transcends binary oppositions of subject and object, modern and traditional, Western and Eastern, people in general and himself as an artist, and transcends the framework of “art” itself within a diverse and vast world where biological and non-biological entities are equal, as described below.

Bricolage as Culture of the Everyday World

I’m not questioning political issues like they thought. I’m actually questioning culture. (Heri Dono)[10]

As these words indicate, Heri Dono consistently highlights the importance of culture as something that cannot be reduced to either art or politics. As one critic wrote, “critical views toward social and political matters, which he touches upon in his works, are expressions relating to everyday problems that people face and that bear cultural significance.”[11] At a deeper level, his approach extends beyond merely expanding “fine art” to encompass visual media such as comics and animation, or pursuing “intermedia” by blending theater, music, dance, and film. Even more broadly, his work embodies bricolage (a term introduced by cultural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss), characterized by assembling inexpensive materials and techniques, regardless of genre, from various disciplines that fall outside the Western category of “art,” including puppet-making, textile and ceramic crafts, and even the work of neighborhood radio repair technicians. This practice represents an expression of primal human creativity.

Based on this inclusive stance that incorporates all forms of culture without distinguishing between high art and folk art, traditional performing arts and contemporary popular culture, or craftsmanship and everyday product manufacturing, it is natural that Heri Dono emphasizes collaboration in creating works that, unlike painting, are impossible for a single artist to realize, requiring complex technology or large-scale installations.[12] The performance Chair in Fukuoka was made possible through collaboration with Kyoto-based Butoh dancer Katsura Kan, jazz musicians from Fukuoka, and university students. In Kuda Binal (Wild Horse, 1992), he had gravediggers from Yogyakarta perform as dancers. In Semar Kentut (English title PhARTy Semar),[13] performed in Auckland, New Zealand, local art students actively participated, while Bangelan at the 2003 Asia-Pacific Triennial in Brisbane incorporated children playing car parts and dishes as instruments. His performance Momotaro, first staged at the 2003 event, was restaged in 2024 at his Kyushu Geibunkan (Art and Culture Center) solo exhibition,[14] featuring musicians from Fukuoka including a gamelan circle, Chikuzen biwa players, and Japanese folk singers along with 31 company employees and housewives recruited through a public open call.

I came to the conclusion that aesthetic feelings reflect collectivity… and this is why I reacted to the common belief in art academies that works of art should reflect individual aesthetic experience. (Heri Dono)[15]

Creation from Folk Culture

This seemingly optimistic stance can be seen as a political and ethical choice with significant implications for the modernization not only of Indonesian art but of society itself, by recognizing the value and creativity within people’s everyday lives and emphasizing collaboration with diverse communities. The origins of this approach can be traced back to the ideology of S. Sudjojono (1917–1986), considered the forefather of modern Indonesian art.[16] In his landmark 1939 essay, Sudjojono rejected the idyllic Mooi Indie landscape paintings created for Western audiences such as the Dutch colonial rulers, and instead called for an art that depicted the real conditions of Indonesian life.[17] Furthermore, gotong royong (mutual aid, helping one another),[18] which is the title of one of Heri Dono’s early paintings, was also a foundational principle of nation-building for President Sukarno, who spearheaded Indonesian independence. In the 1950s and 1960s, Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat (LEKRA, the People’s Cultural Association)[19] led cultural figures to work alongside the people. Also, Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru (the New Art Movement, 1975–79)[20] which Heri Dono encountered as a student, can be considered a turning point in Indonesian contemporary art, introducing an interest in pop art and urban popular culture.[21] Having built his work on a foundation of inheriting and advancing the spirit of Indonesian modern and contemporary art, Heri Dono occupies a historically important position.

Heri Dono’s works have been widely loved around the world not only for their political satire, which may not be easily understood by non-Indonesian audiences, but also for their bold incorporation of traditional artistic styles and techniques, as exemplified by wayang kulit. His art made a great leap beyond the previous framing of Asian contemporary art as merely a derivative fusion of European modernism and local aesthetics. What he references are never merely dead, statically preserved traditions, but a constantly evolving tradition, continuously updated and re-created through the juxtaposition of disparate elements without fear of failure or defeat.[22] His work not only expands the spirit of Indonesia’s modernization but also points toward new paths in art, not only in Asia but across the broader non-Western world.

Here my efforts are towards a tradition that is correct, correct traditions need to be created. So if I make things collide and it’s called failure, I don’t feel that’s wrong… Because art needs to guide culture. (Heri Dono)[23]

(Kuroda Raiji, translated by Christopher Stephens)

Edited, May 2, 2025

NOTES

[1] According to statistics in Stephanie Britton, “Biennials of the World: Myths, Facts, and Questions,” Artlink, vol. 25, no. 3. Jim Supangkat, “The World and I: An Essay on Heri Dono’s Art Odyssey,” The World and I: An Essay on Heri Dono’s Art Odyssey (Jakarta: PT. Mondekorindo Seni Internasional, 2014), 22.

[2] “Chronological Biography of Heri Wardono,” The World and I, 251.

[3] Ibid., 86–88.

[4] On November 12, 1991, Indonesian military forces fired indiscriminately at civilians demonstrating for East Timor’s independence, killing more than 400 people.

[5] Comics and animation that influenced Heri Dono include the American Flash Gordon, the British The Trigan Empire, Indonesian comics such as Petruk Gareng and Put On, newspapers featuring comics like Om Pasikom and Panji Koming, Disney films, Hanna-Barbera cartoons, and puppet animations like Stingray. Information provided to Kuroda Raiji via email by assistant Ayu Astuti (November 14, 2024).

[6] Of the works exhibited at this time, The Artist is Obsessed, Talking of Nothing, and Bad Man were acquired by the Fukuoka Art Museum. From the 4th Asian Art Exhibition in 1994, Watching the Marginal People and Gamelan of Rumor were acquired by the same museum, and these were later transferred to the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum.

[7] In the collection of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum. Another version reminiscent of a Japanese Zen temple, Gamelan of Nommunication (1997/2020), was acquired by NTT InterCommunication Center (Tokyo).

Gamelan Goro-Goro, which deals with the regime change of 1998, is in the collection of the artist.

[8] Made in collaboration with an electrician from Yogyakarta. Due to continuous malfunctions during long-term exhibitions, extensive repairs have been carried out many times, including the addition of control equipment.

[9] Irma Damajanti, “Reading the Personal Aesthetic Codes of Heri Dono,” The World and I, 132.

[10] Supangkat, 73.

[11] Jim Supangkat, “Context,” Heri Dono: Dancing Demons and Drunken Deities, Furuichi Yasuko (ed.) (Tokyo: The Japan Foundation Asia Center, 2000), 98. Original texts edited by the translator.

[12] Regarding the collaborative nature of works by Heri Dono and other Indonesian works, see: Jim Supangkat, “Seeing Collaboration via Works of Indonesian Artists,” The 2nd Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale 2002: Imagined Workshop (Fukuoka: Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, 2002), 144–155.

[13] Semar is one of the clowns appearing in the Indonesian version of the Mahabharata and frequently appears in wayang kulit.

[14] Heri Dono, Komedi dalam Tragedi exhibition (March 9–24, 2024).

[15] Kent, 199.

[16] Kent, 196.

[17] S. Sudjojono, “Painting in Indonesia: The Present and the Future (1939),” The Birth of Modern Art in Southeast Asia: Artists and Movements, Ushiroshoji Masahiro and Rawanchaukul Toshiko (eds.), (Fukuoka: Fukuoka Art Museum, 1997), 204–205.

[18] Regarding the concept of gotong royong, from Sukarno to Ruangrupa, the artistic directors of Documenta 15 (2018), see: Hirota Midori, Kyodo to kyosei no nettowaku, Indonesia gendai bijutsu no minzokushi [A Network of Collaboration and Symbiosis: Ethnography of Indonesian Contemporary Art] (Kurokawa Noriyuki, ed.), grambooks, 2022, 429–435.

[19] Regarding LEKRA, see: Antariksa, “Expand and Strive: Harian Rakjat and LEKRA’s Works,” Blaze Carved in Darkness: Asian Woodcut Movements 1930s–2010s (Fukuoka: Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Arts Maebashi, 2018), 106–107.

[20] Regarding the New Art Movement, see: Hirota, 143–149, and MAM Research 003: Fantasy World Supermarket – Approaches, Practice and Thinking Since the Indonesia New Art Movement in 1970s, Kumakura Haruko, Grace Samboh, and Fukai Atsushi (eds.), Tokyo: Mori Art Museum, 2021.

[21] Supangkat, 49–50.

[22] “Defeat” (which in Indonesian is the same word as “failure”) is an important concept for Heri Dono, and his current studio in Yogyakarta is called Studio Kalahan (Defeat Studio). This name is also based on Detective Harry Callahan, a.k.a. Dirty Harry, played by Clint Eastwood. Damajanti, 122–3.

[23] Personal Interview with Heri Dono, Elly Kent, “The World and I: The Aesthetics of Collision and Failures; Heri Dono’s Participatory Art Projects,” The World and I, 220.