George Keyt

A Distinctive Cubist Style Developed Through Exuberant Line

- Name

- George Keyt

- Media

- Painting

- Region

- Sri Lanka

- Year of Birth

- 1901

- Place of Birth

- Kandy. Sri Lanka

- Year of Death

- 1993

- Place of Death

- Colombo, Sri Lanka

- Link to Art Terms

- Link to Regions

-

Plate of artwork

Mural of Gotami Vihara – 1

Photo courtesy: Ashiwa Yoshiko (photographed in 2019)

Mural of Gotami Vihara – 2

Demons in left of Buddha are depicted in Cubist style.

Photograph by Kuroda Raiji (1986)

Staind glass at Sri Lankan Pavillion, Montreal Expo, 1967.

A Leading Asian Cubist

Cubism, developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque from 1907 onward, influenced artists throughout Asia. Among the European avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, Cubism held a particular appeal for Asian artists, even more so than movements such as Surrealism. One reason may be that it was easier to absorb than oil painting styles rooted in sophisticated realist techniques developed since the Renaissance; another, that its affinity with the flat pictorial space and multiple viewpoints found in many Asian traditions made it especially approachable. While Cubism was pursued by many artists across Asia and took on varied forms from place to place, relatively few succeeded in establishing their own distinctive approach to it. Among those who did was George Keyt, the only artist from South Asia outside India chosen for the exhibition Cubism in Asia: Unbounded Dialogues organized by The Japan Foundation in 2005.

From Academicism to Modernism

In early 20th-century Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), the Ceylon Society of Arts adhered to the academic realism of 19th-century Europe. In 1920, however, Charles Freegrove Winzer (1886–1940) arrived from Britain and remained in Colombo as a drawing instructor until 1932. He introduced Sri Lankan painters to the avant-garde Modernist movements that had emerged in Paris, including Fauvism and Cubism, and founded the Ceylon Art Club. At the same time, Winzer sought to reinterpret ancient Sri Lankan art (such as the 5th-century murals at Sigiriya) in a contemporary context. Keyt joined the club in 1927 and began pursuing painting seriously. The following year, when he exhibited a painting of temple dancers that retained traces of a European academic style, its sensuality caused a scandal, the first of its kind in Sri Lanka. Even in his later stylized depictions of women, sensuality remained an underlying theme, as it did in the work of Picasso.

Keyt gradually absorbed Modernist art through Winzer, including Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Picasso, Braque, Fernand Léger, and Henri Matisse. The photographer Lionel Wendt (1900–44) also energized young artists such as Keyt with the knowledge of cutting-edge avant-garde art he had gained during his studies in Europe, as well as through publications like the French art magazine Cahiers d’Art. From 1933 onward, the influence of Cubism became clearly visible in Keyt’s work. His still lifes were noted for their resemblance to those of Braque, but the compositions constructed from long, sinuous lines that move across the canvas in what can feel like a single continuous stroke, which he developed in later years, were entirely his own.

Experimentation with Buddhist Temple Murals

Key factors behind Keyt’s Sri Lankan variations on the modernist art that emerged in Europe include his birth to parents of European descent[1] in the old capital of Kandy, known for Sri Dalada Maligawa (the Temple of the Tooth), and his early familiarity with Buddhist temples and monks. His extended stays in India in 1939 and 1946 also had a strong impact on his style. His admiration for Buddhist and Hindu art, including the murals and sculptures at Sigiriya, Anuradhapura, and Polonnaruwa in Sri Lanka, now designated UNESCO World Heritage sites, as well as the murals at Ajanta in India, helped shape a uniquely South Asian modernist style.[2]

When Keyt was 24, Maligawage Sarlis (1880–1955), who came from a caste associated with painting and other artisanal trades, issued color lithographs of Buddhist imagery, and in the same year a landmark publication tied to the Buddhist reform movement and Sinhala Buddhist nationalism also appeared.[3] While political elements are difficult to discern in Keyt’s paintings, his Buddhist faith should be viewed in the context of an era shaped by nationalism and ethnic movements.[4]

Keyt’s most important involvement with Buddhist art is the mural he produced from 1939 to 1940 at Gotami Vihara Temple near Colombo. Depicting the life of the Buddha, the mural fills the wall with groups of figures shaped by layered, fluid curves, revealing that even before he established the style associated with his work of the 1940s, Keyt had already developed a way of deploying a strong visual rhythm across the surface.[5] Another notable element is that, unlike the ordered figures of Kandy temples, the scenes are not punctuated by architectural structures but connected by decorative patterns of drapery and floral designs that overflow from one scene to the next. In this mural, the volume of women’s bodies is emphasized, yet more striking still is the treatment of the demons’ faces, rendered in sharp, linear forms with a Cubist inflection, each differing in a way that introduces intentional dissonance. In a close reading, this could be taken as a nationalist gesture, casting the European power signified by Cubism as a force of evil to be countered through Sri Lankan Buddhism. The rejection of British academicism, which had been dominant before the ’43 Group (a modern art circle formed in Colombo in 1943), may indeed have expressed anti-British, anti-colonial, and nationalist sentiment. Considering that Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948 as the Dominion of Ceylon within the British Commonwealth, the ’43 Group was likely connected in some way to the broader movement toward independence.[6]

The Buddhist mural style pioneered by Keyt was carried forward by later Sri Lankan painters, including younger members of the ’43 Group such as Stanley Kirinde.

The ’43 Group and Beyond

In 1943, Keyt took part in the first exhibition of the ’43 Group, held that November. The group had been formed at the urging of Lionel Wendt, with members including Geoffrey Beling (1907–1992), Justin Deraniyagala (1903–1967), and Harry Pieris (1904–1988). In a manifesto, Winzer called for adapting the traditional art of ancient Buddhist sites such as Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa to contemporary practice. His observation that “the continuity is closer to the decorative conception of modern art than to the realistic, true-to-life prettiness and cheap harmonies of academic achievement”[7] is also illuminating in terms of why Cubism, as noted earlier, held such strong appeal for many Asian artists.

The work of the ’43 Group, which can be regarded as the earliest modern art group in South Asia, was derided in Sri Lanka at the time as incomprehensible. After Wendt’s sudden death the year after the group was formed, however, Harry Pieris assumed leadership, and the group gradually gained recognition in Europe through exhibitions in London in 1952, in Paris the following year, and at the 1956 Venice Biennale, where Deraniyagala received an award.

The Indian arts and culture magazine MARG,[8] founded in 1946, published two articles on Keyt in its April 1947 issue, featured Ceylon and the ’43 Group in its April 1952 issue, and often reproduced Keyt’s works.[9] The magazine’s founder, Mulk Raj Anand, was a supporter of India’s first modernist art group, the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group, established in 1947, and, as chairman of India’s national academy of arts Lalit Kala Akademi, launched the Triennale-India in 1968. A novelist by profession, he played a central role in advancing modernism and internationalization in Indian art.[10] Keyt’s 1947 solo exhibition in Bombay and the recognition accorded to the ’43 Group were also evidently shaped by Anand’s outlook.

The ’43 Group supported Keyt, Deraniyagala, Ivan Peries (1921–1988), and others, fostering their talents, but the group began to wane in the late 1960s and eventually disbanded. One reason was that after the government designated Sinhala as the sole national language in 1961, many members who were English-speaking Burghers (see endnote 1) of European descent, including Peries, emigrated to Canada, Europe, or Australia.[11] A deeper reason may have been that most members belonged to the upper class, did not need to work for their livelihood, and lacked a connection to the wider population. The Sri Lankan art critic H. A. I. Gunatileke observed that they “did not witness the realities of rural life and could not produce imagery that spoke to those outside the cities.”[12]

The Maturation and Decline of Keyt’s Style

Keyt received particularly high acclaim within the ’43 Group, and his style reached its most fully realized form in the 1940s during the group’s formative years. His method of dividing up the composition with long, sweeping curves, within which female figures and still-life elements take shape, differs from the analytical approach of early Cubism, which combined multiple perspectives on three-dimensional objects or broke subjects into semi-transparent planes of color. The pairing of a profile nose with frontal eyes, familiar from the work of Picasso and often found in that of Keyt, may also have a symbolic connection to the union of Radha and Krishna (female and male) in Hindu mythology.[13]

From around 1950, however, Keyt’s compositions grew dense, overworked, and crowded with figures, and especially in works produced after the 1970s, the unity once created by the dynamic curves that seemed to cut across the canvas in his paintings of the 1940s, the “inventive modernist forms etched in rhythmic flowing lines,”[14] disappeared. His style ceased to evolve and fell into repetition.

At the same time, his reputation in Sri Lanka continued to grow,[15] and in 1954 he gained international visibility through an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London organized by the eminent critic Herbert Read, while his works were also shown in major Indian cities such as Bombay, Delhi, and Madras.[16] His works were acquired by the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Keyt lived to the age of 92 as one of Sri Lanka’s leading painters, producing stained glass for the Sri Lanka Pavilion at the 1967 Montreal Expo, among other projects.

The George Keyt Foundation was formally established in 1990 and has since continued its work promoting art and literature in Sri Lanka.

Derivative Eclecticism or Originality?

When Keyt exhibited in Europe, some venues even refused to show his work on the grounds that it looked too much like Picasso. Such judgments, however, were bound up with Eurocentrism that “did not recognize autonomous, self-directed modernism which could reinvent itself in each country where it was located.”[17] Keyt was incensed by these reactions:

How silly about Picasso and my work being like his! Have they ever seen the Kalighat pictures – traditional – of Bengal, or the Hindu sculpture, especially of the South, or the Basohli and other fine miniature works (…) They are all so used to seeing and hearing about Picasso (…) that anything not academic in the European sight is Picasso![18]

The Japanese, who are far more familiar with the work of Picasso than with traditional Asian art, may be among the targets of Keyt’s indignation. When we survey 20th-century art across Asia, there are few artists aside from Keyt, who peaked creatively in the 1940s, who succeeded in fusing post-Cubist modernist approaches and local traditions in a compelling formal synthesis. Perhaps the closest parallels are Jamini Roy in India, who incorporated the styles of Bengali folk art, and Kim Whanki in Korea, who applied abstraction to traditional subjects such as vessels, moons, and mountains. As discussion continues over whether such artists achieved originality that moves beyond Western precedents rather than producing something merely eclectic or derivative, Keyt’s work stands as a vital milestone in the history of modern Asian art.

(Kuroda Raiji, translated by Christopher Stephens)

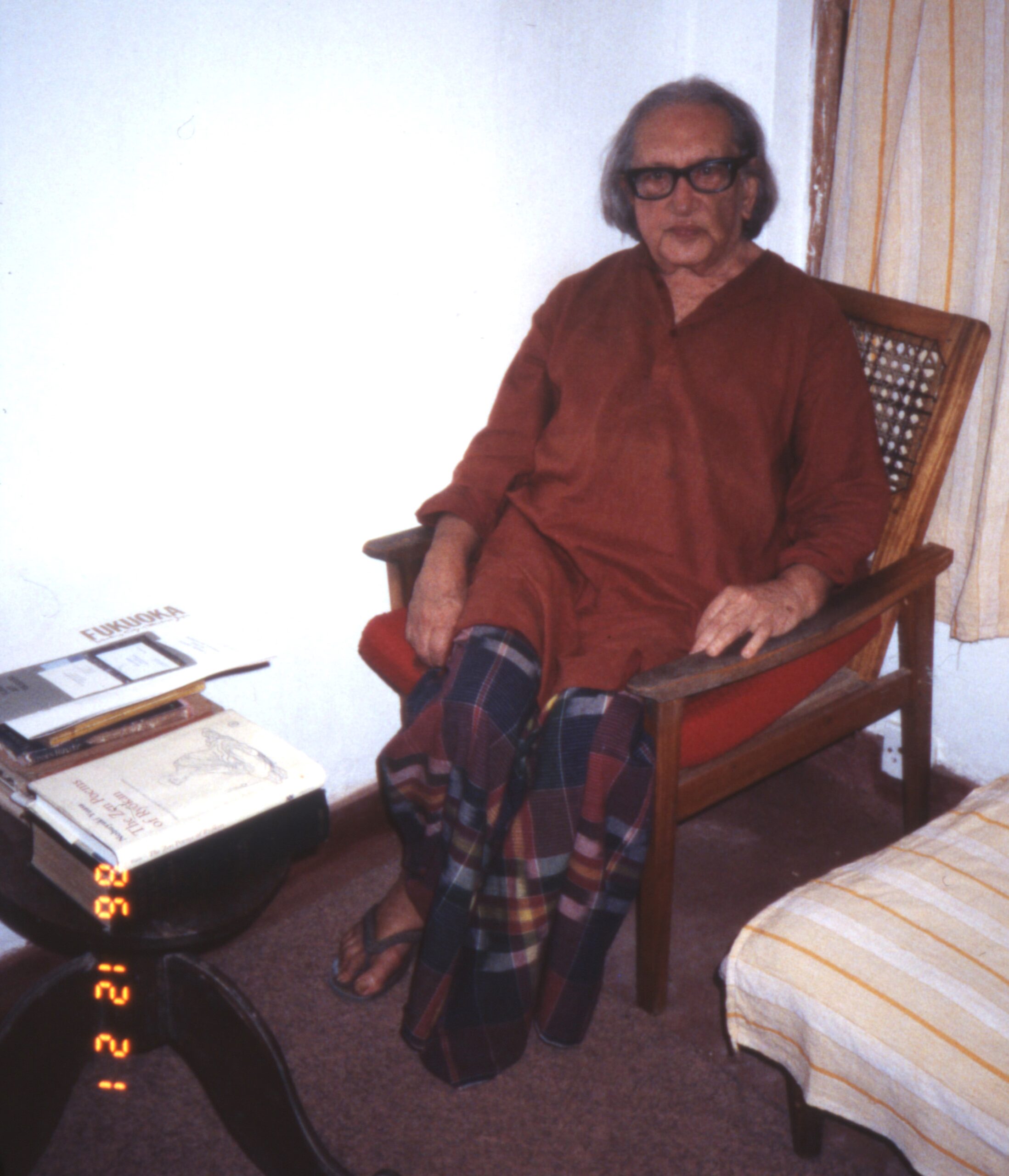

Portrait of the artist by the author (1986)

[1] Descendants of Portuguese, Dutch, and British residents in Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) formed an elite class known as Burghers. Keyt’s lineage is unclear, with theories including British, Dutch, Portuguese, and Jewish ancestry. Yashodhara Dalmia, Buddha to Krishna: Life and Times of George Keyt (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 3–7. The photographer Lionel Wendt was a Dutch Burgher.

[2] Keyt was born into a Christian family, aspired to become a Buddhist monk, also identified as Hindu, and is said to have converted to Islam in order to marry his last wife. He appears to have had a tolerant attitude toward religious difference. See Dalmia, 55.

[3] Ashiwa Yoshiko, “Murals of Buddhist Temples and Modern Allegories: Image Houses in Post-Conflict Sri Lanka,” NACT Review: Bulletin of the National Art Center, Tokyo, No. 3, National Art Center, Tokyo, 2016, 96.

[4] Dalmia, 54.

[5] Dalmia, 53.

[6] However, as Keyt and others later embraced Cubist methods more fully, their work inevitably occupied what Weerasinghe describes as “an ideologically precarious position,” unable to break free from following European models. Jagath Weerasinghe, “A Survey on the ‘Presence’ of Cubist Sign / Idiom in Sri Lankan Art,” in Cubism in Asia: Unbounded Dialogues, edited and published by the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo and The Japan Foundation, 2005, 264.

[7] Neville Weeraratne, 43 Group: A Chronicle of Fifty Years in the Art of Sri Lanka (Melbourne: Lantana Publishing, 1993), 16.

[8] MARG is an acronym for Modern Architectural Research Group.

[9] Dalmia, 103.

[10] Dalmia, 101-2.

[11] Dalmia, 205, 211.

[12] Dalmia, 211.

[13] Martin Russell, “George Keyt,” George Keyt: A Centennial Anthology (Colombo: The George Keyt Foundation, 2001), 6.

[14] Dalmia, 175.

[15] An anecdote illustrates Keyt’s fame at this time. In 1954, actress Vivien Leigh, known for Gone with the Wind, visited Keyt and purchased his work while staying in Sri Lanka for the filming of Elephant Walk. Leigh subsequently fell ill, and Elizabeth Taylor took over the role. Keyt’s work could not be located after Leigh’s death, and its whereabouts are unknown. Dalmia, 43–44.

[16] Critiques were not uniformly favorable when Keyt’s works were shown in Europe. Art critic John Berger, who viewed the ’43 Group exhibition in London in 1952, wrote scathingly: “He gathers together elements from Picasso, the Indian cave paintings at Ajanta and the Sinhalese at Sigiriya… He lacks the fire to fuse the elements together because his mood is too nostalgic and his observation too schematic.” By contrast, a solo exhibition by Keyt at another London venue around the same time received high praise: “In Sinhalese and Indian mythology he has found themes capable of expressing a modern philosophy of life through his own emotional and poetic imagery.” Dalmia, 153–4.

[17] Dalmia, 190–1.

[18] Dalmia, 191–2.