Penang Chinese Art Club and the Society for Chinese Artists

Chinese Artists’ Movements in Malaya

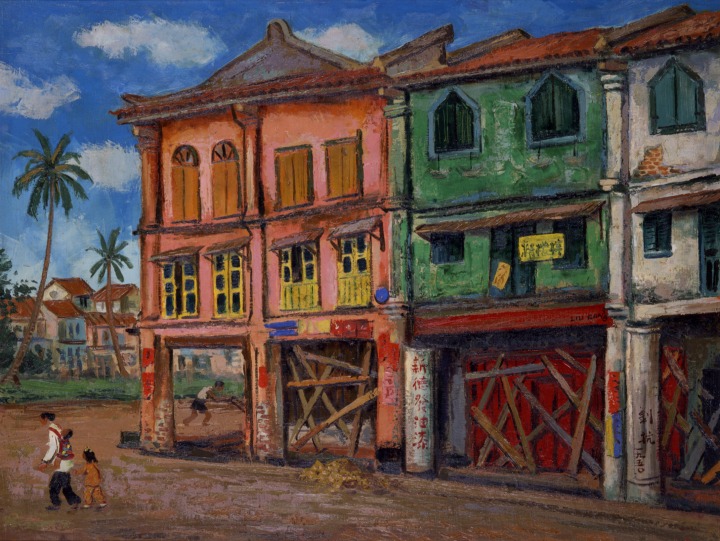

The 1930s saw a growing trend of nationalism as countries in Southeast Asia won their independence from colonial powers. The modern art movement grew alongside the question of ethnic identity. However, the modern art movement in British Malaya (present-day Malaysia and Singapore) was different from that of other countries: the actors involved in this movement were not indigenous Malays but Chinese migrant artists. Unlike other countries, where the art movement grew together with nationalism, the movement in British Malaya grew from a sense of belonging to the Chinese community. The leading groups of the movement were the Penang Chinese Art Club (founded in 1935) and Singapore’s Society for Chinese Artists (founded in 1936), and Yong Mun Sen (1896–1962) and Tchang Ju Chi (1904–1942) played central roles in the two groups. In 1938, these groups established the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts in Singapore. Furthermore, art education for the children of the Chinese community commenced under the leadership of Lim Hak Tai (1893–1963). However, the prewar art movement was suspended due to the Japanese invasion of the Malay peninsula, and a few young talents, including Tchang Ju Chi, died in the Japanese prisoner of war camp in Changi. After the war, the Society for Chinese Artists restarted under the leadership of Liu Kang (1911–2004), and newly migrated artists, including Georgette Chen (1907–1992), Chen Wen Hsi (1906–1991), and Cheong Soo Pieng (1917–1983), led the art scene while teaching at Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. During this time, Post-Impressionism and Fauvism—especially the styles of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin—became popular. Artists depicted the Nanyang climate and landscape using the vivid and strong touch of Gogh and Gauguin, portraying women in the Malay peninsula and Indonesia the way Gauguin depicted women in Tahiti from the perspective of orientalism. Yong Mun Sen’s Lady of Dignity is one such example. At the same time, the artists focused on their Chinese identities. Liu Kang states, “I thought that the Chinese ink line drawing was my core.” In Kang’s Slippers, black lines move here and there in a feast of colors and shapes, indicative of what he meant by “Chinese ink line drawing.” Lines also play a crucial role in the composition of Georgette Chen’s Cityscape of Beijing.

[Rawanchaikul Toshiko]

Yong Mun Sen "Lady of Dignity" 1931 oil on canvas and board

Liu Kang "Old Street" 1950 oil on canvas